Battle for Crimea Rages On

By

Lubomyr Luciuk

I did not expect the call of a muezzin

in Simferopol.

Not that hearing the chosen being invited to their devotions troubles me. I

appreciate this caution against allowing the commerce of daily life to distract

one from giving thanks to God. Yet other residents of this Crimean city find

the five-times-daily summoning of Muslims to prayer, the adhan,

worrisome. It reminds them that ownership of this peninsula is contested. They

forget one thing – it always has been.

Nearly the size of Belgium, Crimea

historically was a bridgehead connecting the empires of the Eurasian steppes

with those of the Black sea

and Mediterranean sea

basins. Invaders have come and gone – ancient Greeks and Scythians, Rome’s

legions, then Goths, Huns, Khazars, Byzantines, various Turkic nomads,

Venetians, Genoese, Ottoman Turks and, finally, Tsarist Russia’s armies,

conquering in 1783.

That gateway role is

reflected in Crimea’s

history. In 988 in Chersones, now part of Sevastopol,

Kyiv’s Prince Volodymyr converted to Christianity, then that faith was diffused

among the East Slavs.

Today, the region’s vistas are pleasant – vineyards covering gently rolling

hills and wide valleys – but this very same terrain witnessed the Ukrainian

Cossacks of the Zaparozhian Sich fight marauding Tatars and resist Ottoman

encroachment. And Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “The Charge of the Light Brigade”

immortalized the disaster that befell another band of cavalry near Balaklava in

1854. Heroically interpreted by Errol Flynn in his 1936 film of the same name,

this Hollywood version of that Crimean War battle left at least one young boy

begging his mother to take him to their local public library, to read that

paean in its entirety – the first time I sought out poetry.

In 1919-1920, this headland

became a bastion for the anti-Bolshevik White Army of General Denikin, a point

d’appui for foreign military interventions unsuccessfully deployed against

Lenin’s regime. Crimea

was next overrun by the Nazis, in 1942, then suffered cultural genocide in May

1944 when the Soviets returned and deported the Tatars because of their

supposed disloyalty during the German occupation. Stalin is said to have

contemplated a similar treatment for Ukrainians, a deed left undone only

because there were too many of them. And at Yalta, Eastern

Europe’s postwar fate was sealed in February 1945

when Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt met in the Livadia Palace to

carve out the ‘spheres of influence’ that shaped Europe’s

geopolitics for another half century.

Soviet Ukraine

acquired Crimea in

1954 after Nikita Khrushchev transferred the property’s legal title from the Russian

Soviet Federated Socialist Republic, a gift marking 300

years of allegedly fraternal relations between these two distinct nations. It

was a hollow gesture as Crimea

remained in the USSR

and no one then envisioned the Soviet empire’s collapse or an independent Ukraine.

As for the Tatars, permitted to trickle back from Central Asian exile only at

the end of the Soviet period, they began returning in greater numbers after

1991 when Ukraine’s government tried to redress the historical injustice they

had endured, even though that crime was of Moscow’s making, not Kyiv’s. Still,

Crimean society remains Russified, retarded by a relic Soviet mentality akin to

the one most of Ukraine’s eastern marches wallow in, an ignorance fuelling

Ukraine’s current drift away from Europe. So, Lenin statues stand prominent in Simferopol, Sevastopol,

and Yalta.

Asking why, I was told: “We were allowed to dump Communism but had to keep

Lenin.” They have not really rid themselves of either.

Making matters worse are

revanchists campaigning to bag Crime for ‘Mother Russia.’ Dozens of billboards

proclaim Crimea’s

future prosperity lies in reunification, a blatantly secessionist placarding

not being countered by Kyiv. The very few posters heralding Ukrainian President

Viktor Yanukovych as Crimea’s

hope, and Ukraine’s,

are in Russian only. Perhaps the President’s propagandists have their countries

confused.

Will Crimea’s

status remain uncertain? Maybe there’s an answer in what I found in a madras,

an Islamic school, in Bakhchisaray. There, I saw a mullah instructing a

small group of children, young boys and girls learning the Koran

together. I asked in Ukrainian if I might take their photograph. When the

Turkish teacher replied that he spoke no Russian, one of his pupils, a girl,

aged 11, began translating – in perfect Ukrainian. Aware of her Crimean Tatar

heritage and Islamic faith she also proudly identified herself as a Ukrainian.

If more of her fellow citizens did likewise, Ukraine

might still make it back to Europe.

Lubomyr Luciuk, PhD., teaches political

geography at the Royal Military College of

Canada

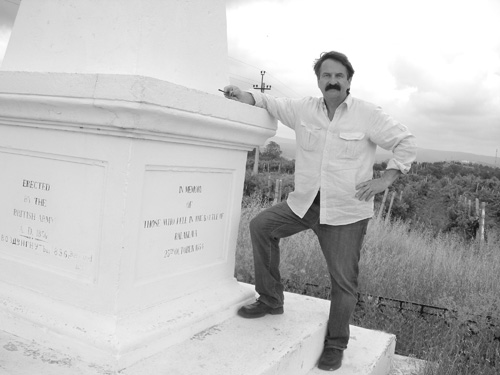

PHOTO

Lubomyr Luciuk at the British Army Memorial of the Battle of Balaklava in Crimea